The most famous wrestler in the world at one time started Hulkamania while in the Twin Cities-based American Wrestling Association.

The Minnesota Star Tribune

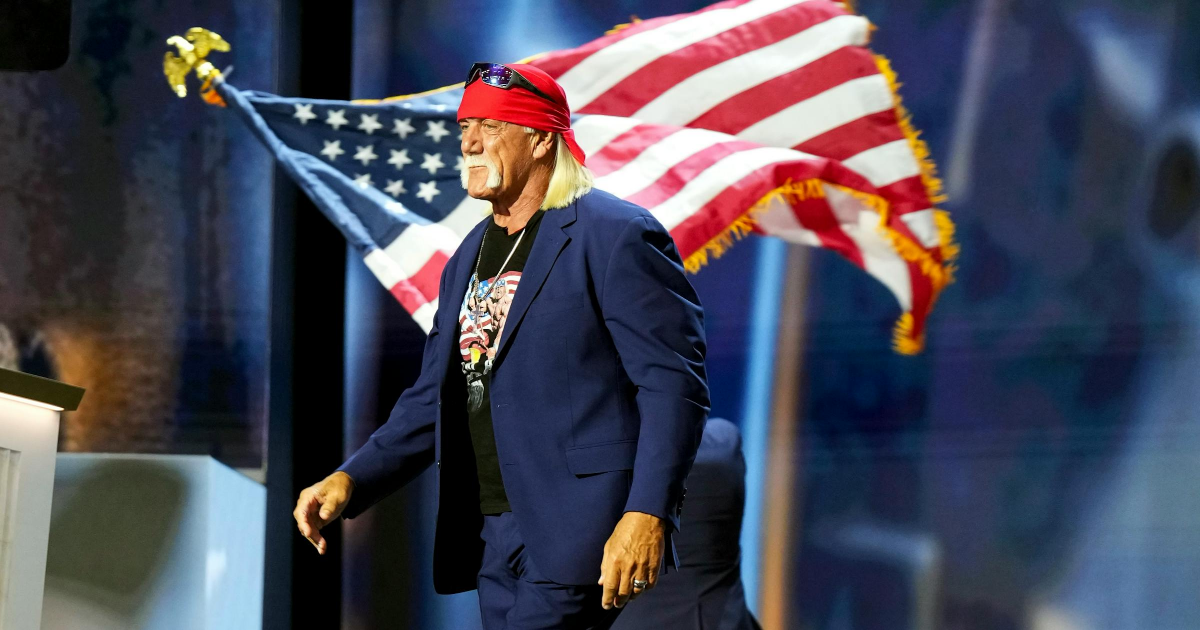

Retired professional wrestler Hulk Hogan takes the stage to speak during the final day of the Republican National Convention at the Fiserv Forum in Milwaukee in July 2024. (Glen Stubbe/The Minnesota Star Tribune)

Comment

Hogan died Thursday at 71. He was hired by the Minneapolis-based American Wrestling Association (AWA) in 1981 after struggling to gain traction with the World Wrestling Federation (WWF). In two short years, Hogan would make the switch from being a bad guy to becoming arguably the most beloved wrestler in the Midwest, testing out the traits that led him to become a pop culture icon in the 1980s.

Hogan, whose real name was Terry Bollea, was a larger-than-life presence who garnered mainstream appeal and became the best-known professional wrestler of his day. He was more known later in life for his legal battles, troubling racial issues and exaggerations while talking about his already-wild career.

Yet one thing is true: Without his time in Minnesota, the Hulkster wouldn’t have become the face of pro wrestling that he was for decades.

Hulk Hogan rips his shirt off in preparation for his bout with Big Bubba at the Mall of America in 1999. (DAVID BREWSTER)

The man behind Hulk Hogan was about five years into his professional wrestling career by the time he moved to Minnesota in 1981 at the invitation of Verne Gagne, the promoter and longtime champion of the AWA. Before he was Hulk Hogan, he wrestled as Sterling Golden and Terry “The Hulk” Boulder for several years in the eastern U.S., eventually landing with the New York-based WWF.

Then-WWF promoter Vince McMahon Sr. came up with the name Hulk Hogan, combining “The Hulk” with an appeal to Irish fans. A popular story says McMahon Sr. soured on Hogan for agreeing to be in “Rocky III” as Thunderlips, the wrestler who challenged Rocky Balboa in a charity match.

The story goes McMahon Sr. fired Hogan for trying to step outside the pro wrestling world on his own.

“I was talking with Vince Sr. about doing ‘Rocky III,’ and Vince Sr. says ‘You’re not doing that. You’re a wrestler. … You don’t act, you don’t do TV stuff,’” Hogan said in the 2024 Netflix documentary “Mr. McMahon,” about Vince McMahon Jr.

“He goes, ‘If you do that, you’re fired, and you’ll never work here again.’ I said, “OK, cool.’”

Minnesota wrestling historian George Schire disputes this account, however.

“When Hogan was here, it was a short time afterwards where he was Thunderlips in the movie,” Schire said. “That had nothing to do with the WWF at the time at all.”

A still from “Rocky III” where at a charity wrestling match, Rocky (Sylvester Stallone) faces the giant Thunderlips (Hulk Hogan).

Hogan was dissatisfied with his time in the WWF, according to Schire, and approached Gagne to come to the AWA in Minnesota. When he came into the wrestling territory, he was still working as a “heel,” or a bad-guy wrestler.

At the time, the AWA held shows throughout the upper Midwest, with key events in the Twin Cities, Milwaukee and Chicago. While Hogan’s size, muscles and blond look made the fans cheer rather than boo him, he wasn’t ready for the main events when he came in.

Gagne had Hogan work on his talking skills with announcers like “Mean” Gene Okerlund and wrestling managers like Bobby “The Brain” Heenan to help find Hogan’s trademark manic voice. At the same time, Hogan took inspiration from another flamboyant personality in Superstar Billy Graham, the charismatic musclebound heel who openly boasted of using steroids to enhance his physique and who beat Bruno Sammartino for the WWF Championship in the 1970s.

“(Graham) had a gift of gab that no other wrestler at that point had,” Schire said. “He was the influence for a guy like Hulk Hogan … he admitted that Superstar Graham was an idol, he loved the image, the character, and then Jesse Ventura later said the exact same thing.”

In short order, Hogan became a wrestling favorite. The release and box office success of “Rocky III” cemented Hogan’s star in the audience’s eyes. And fans were already starting to buy “Hulkamania” shirts, which Hogan was starting to rip off his body during interviews.

Hogan challenged several times for the AWA championship, but never actually captured the title. He came closest when he faced Nick Bockwinkle on April 18, 1982, at the St. Paul Civic Center.

Hogan won, but he had thrown Bockwinkle over the top rope during the match, which was a disqualification according to the rules at the time. AWA President Stanley Blackburn threw out the decision, allowing Bockwinkle to keep the belt.

Hogan remained on top of the AWA for another year before leaving in controversial fashion for the WWF at the end of 1983.

McMahon Jr. had by then bought out the WWF from his father and was looking to take his promotion national, riding the advent of cable TV to expose homes across the U.S. to WWF wrestling. At the time, pro wrestling was divided into territories, with AWA just one of about two dozen major promotions across the U.S. and Canada.

McMahon had kept tabs on Hogan and planned to promote him as the WWF’s star. But Hogan was comfortably finding success in the AWA, where he was close to capturing the AWA championship and beating international stars like Antonio Inoki in Japan.

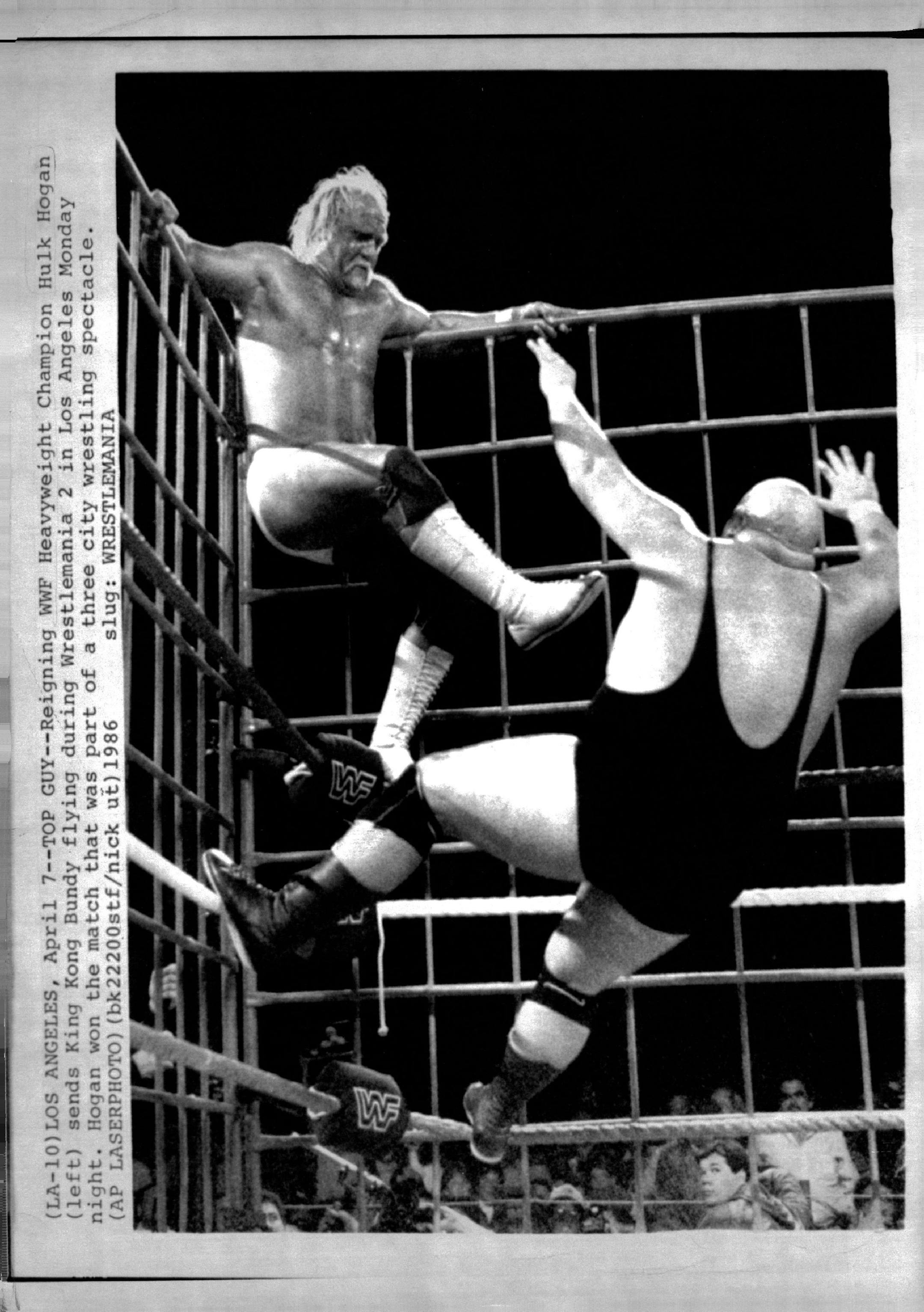

Top Guy-Reigning WWF Heavyweight Champion Hulk Hogan, left, sends King Kong Bundy flying during Wrestlemania 2 in Los Angeles in April 1986. Hogan won the match that was part of a three-city wrestling spectacle. (Nick Ut)

Hogan was advertised to wrestle his longtime nemesis, “Dr. D” David Schultz, at a Christmas show at the Civic Center. Shortly before bell time that day, Gagne received a telegraph from Hogan, saying he was jumping to the WWF.

“When (Gagne) asked why, Hogan said, ‘Vince McMahon has paid me to stay away, and I’m not going to come back to work in the AWA,’” Schire said. “That’s the true story.”

Hogan would also take Schultz and Okerlund, the announcer, with him to the WWF. A few weeks later, on Jan. 7, 1984, he defeated the Iron Sheik to capture the WWF championship, beginning his ascent to superstardom.

Hogan would return to Minnesota over the years as the biggest star in the WWF, but he made one more major wrestling impact in Minnesota in the 1990s.

McMahon and the ongoing pressures of TV deals had driven the AWA out of business by the end of 1991, but a new challenger rose to take on the WWF in World Championship Wrestling.

WCW was owned by Ted Turner, who gave permission to TV executive Eric Bischoff (who also got his start in the AWA as an announcer) to run weekly wrestling shows against the WWF. Bischoff created “Monday Night Nitro,” which debuted Sept. 4, 1995, at the Mall of America.

Hogan wrestled Big Bubba Rogers (who later became the Big Boss Man) that night and promoted his new Pastamania restaurant inside the mall. WCW would dominate pro wrestling for several years in the ’90s before mismanagement and money issues caused them to lose ground to the WWF. WCW closed in 2001; McMahon bought the company and turned his own promotion into World Wrestling Entertainment.

Hulk Hogan wrestles Big Bubba at the Mall of America in September 1995, while his trainer wrestles the referee. The crowd, who jammed all four levels of the rotunda area, loved it. (DAVID BREWSTER)

Hogan returned to WWE soon after, wrestling for several years in the mid-2000s before hanging up his boots by 2010.

He was briefly banished from the WWE during the 2010s after racist remarks he made toward Black people came to light during his lawsuit against Gawker Media, but he had begun to be an ambassador for WWE once more in recent years.

His last televised appearance with the WWE was in January of this year on the debut episode of “WWE Raw” on Netflix.

With Hogan’s passing, there likely won’t be another professional wrestler who could capture the world’s attention like he could.

“Whether you liked him, hated him or whatever, he was the biggest thing that ever happened to pro wrestling,” Schire said.