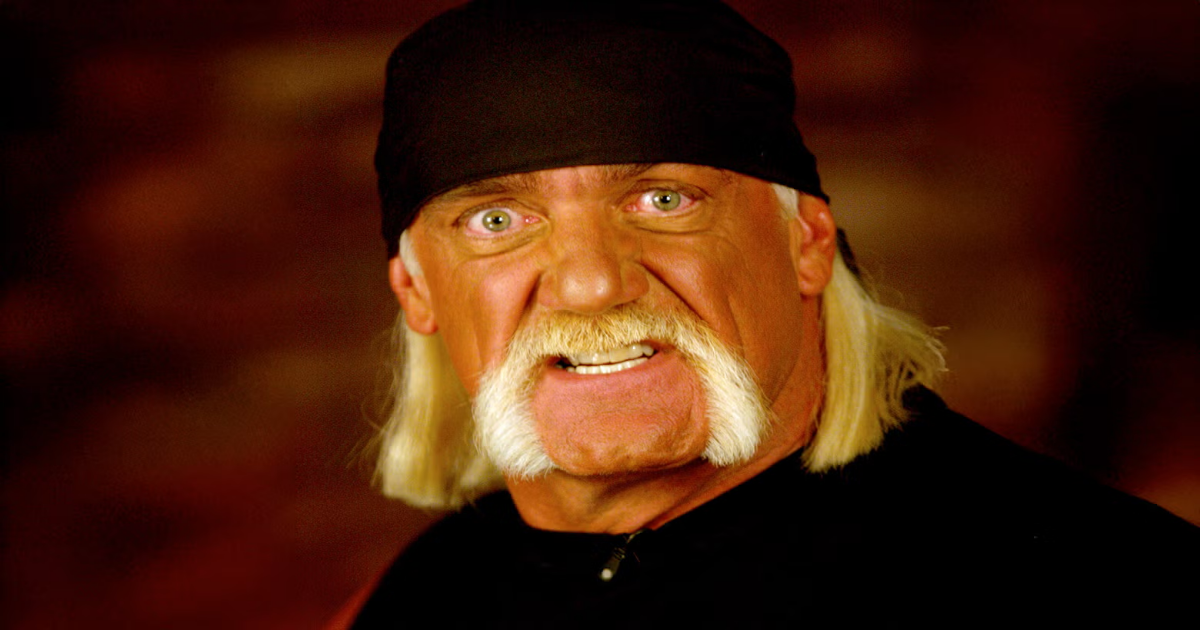

Before I say a whole bunch of mean things about the man, let me clear the air. Hulk Hogan, who died early Thursday at 71 of apparent cardiac arrest, was one of the greatest professional wrestlers of all time. Even now—decades removed from his apex as a performer—Hogan remains the art form’s single most iconic cultural presence. He reached an echelon of fame previously unheard of in the squared circle. It isn’t an exaggeration to say that without his red-and-yellow gestalt clearing the way, guys like Dwayne “the Rock” Johnson and John Cena would’ve struggled to make a dent in Hollywood. Hogan was a consummate performer—never a technical wiz between the ropes, but preternaturally gifted with a unique brand of cartoon machismo. He occupies the Washington spot on the WWE Mount Rushmore. Nobody else comes close.

But if we’re going to write an honest accounting of the man’s life, we must acknowledge the other piece of the Hogan legacy. I speak, naturally, of how, by the end of his life, everyone seemed to hate his guts.

I am not talking about Hogan’s latter-day MAGA turn, though that certainly didn’t help. (He appeared at last summer’s Republican National Convention, where he tore off his shirt and flexed for the cameras in a Trump–Vance tank top.) It turned out to be a publicity stunt: Hogan was in the process of launching his Real American Beer, and he seemed eager to enshrine himself on the right side of the forthcoming realignment. Hilariously, that meant that one of his final stints on WWE television occurred days before the inauguration, during which he shilled his beer to a spectacular viral cascade of boos from wrestling fans. (I wrote about the spectacle when it happened. It might be the only joy that the second Trump administration has brought me.)

Hogan would later claim that he was jeered for his “political beliefs,” casting himself as a beleaguered warrior standing athwart an encroaching liberal tide. Nothing could be further from the truth. Why do people despise Hogan? You need simply look at the cavalcade of hurt feelings and callous double-crosses he left in his wake. In a career spanning half a century, the man developed a genuinely Jay Leno–like reputation for the viciousness in which he protected his top spot in World Wrestling Entertainment. His ego frequently degraded the product itself.

There are too many stories to recall here, and all of them require a certain fluency with pro-wrestling customs, but I’ll try to distill a few highlights in layman’s terms. For instance: In 1993 Hogan outmaneuvered Bret Hart—another one of the greatest wrestlers of all time—by persuading company Chairman Vince McMahon to alter the ending of WrestleMania IX at the last minute. Instead of Hart defending his title in the main event, Hogan snatched the belt back on an anticlimactic technicality. Hulk paraded around the gold for the last few months he had left on his contract, in a farewell tour only he seemed to want. Hart never forgave him.

An even weirder incident occurred four years later, when Hogan was working for WWE’s rival wrestling promotion WCW. He was playing a bad guy at this point in his career, and he was booked to wrestle the beloved babyface Sting. It was, legitimately, the most anticipated match of its era, and the company cloaked it in all sorts of soap-opera pageantry. The storyline, heading into the match, was that Hogan had skewed the rules to his favor with a crooked referee named Nick Patrick. Patrick was supposed to execute what is known in the industry as a “fast three count.” When Hogan pinned Sting, Patrick would pound the mat as fast as possible to award Hogan the victory—thus ditching the impartial cadence enforced by the imaginary rulebook. It would demonstrate to the crowd, in no uncertain terms, that its hero had been screwed out of his rightful victory.

The one problem? When the match reached its climax, Patrick didn’t perform a fast three count after all. There are conflicting reports on why, but years later Patrick alleged that Hogan was the one to call the audible. At his most ruthless, it could often seem like Hogan believed wrestling to be real.

To be fair, he was not alone in that distinction. Pro wrestling has always been a cutthroat institution and, historically speaking, has favored its most cold-blooded operators (Shawn Michaels, Stone Cold Steve Austin, and even the Rock all come to mind). But Hogan’s crimes had a nasty way of escaping the fantasia of the ring.

In 1986 Hogan committed perhaps his greatest sin, when he scuttled a burgeoning unionization effort in the WWE. The labor action was led by future Minnesota Gov. Jesse “the Body” Ventura. He planned to organize a wildcat strike in the days before WrestleMania II, when the performers had maximum leverage. (Health care and retirement benefits were among his core demands.) After Hogan caught wind of the effort, he took it straight to McMahon, who subsequently threatened to fire any wrestler involved in the effort. Just like Hart, Ventura never made amends with Hogan, who characterized what he did as a betrayal. To this day, WWE wrestlers lack a union.

I could go on. Hogan was the vessel for one of Peter Thiel’s first forays into political donorship, when the tech baron dumped oodles of cash into a lawsuit that brought about the destruction of Gawker Media. Hogan was suing the publication ostensibly because it had published his sex tape, on which he uttered racial slurs, specifically about the Black man his daughter Brooke was dating. In reality, it seemed clear he was Thiel’s willing partner to take down a longtime foe. Still, the slurs got him briefly booted out of the WWE, and when the company reinstated him in 2018, he offered a half-hearted mea culpa to a the wrestlers back stage. According to those present, Hogan began his apology by warning the roster to be mindful about being recorded without their knowledge, rather than addressing the charges head-on. A group of prominent Black wrestlers eventually released a statement about the meeting, asserting that they’d need to see Hogan make a “genuine effort to change” if he were to gain their trust again. (It is safe to say that that never happened.)

So this is where we leave Hogan—a conniving and sadistically opportunistic person who is, nonetheless, permanently sanctified in the canon. I’m sure if you had the chance to ask him, he’d contend that all of those qualities were vital to his success, that it is impossible to scale the oily theogony of pro-wrestling immortality without making a gallery of enemies, both on-screen and off-. The trade-off? Unlike so many of his peers, Hogan never did earn a beatific final chapter. Nobody came to kiss the ring. Those glory years in the 1980s, when Hulkamania truly ran wild, have been completely overshadowed by his cruelty. Toward what we now know was the end of his life, fellow legends seemed to take special pleasure in offering parting potshots. Just days ago, I listened to the Undertaker give his opinion on the hellish reception Hogan received in Los Angeles: “Sometimes in life, things come back.”

Get the best of movies, TV, books, music, and more.