Sign up for the Slatest to get the most insightful analysis, criticism, and advice out there, delivered to your inbox daily.

On Wednesday, we wrote about how CEOs were starting to get buyer’s remorse about Donald Trump, the presidential candidate that many of them supported despite his promises to impose what essentially every economist in the world said would be market-crippling tariffs.

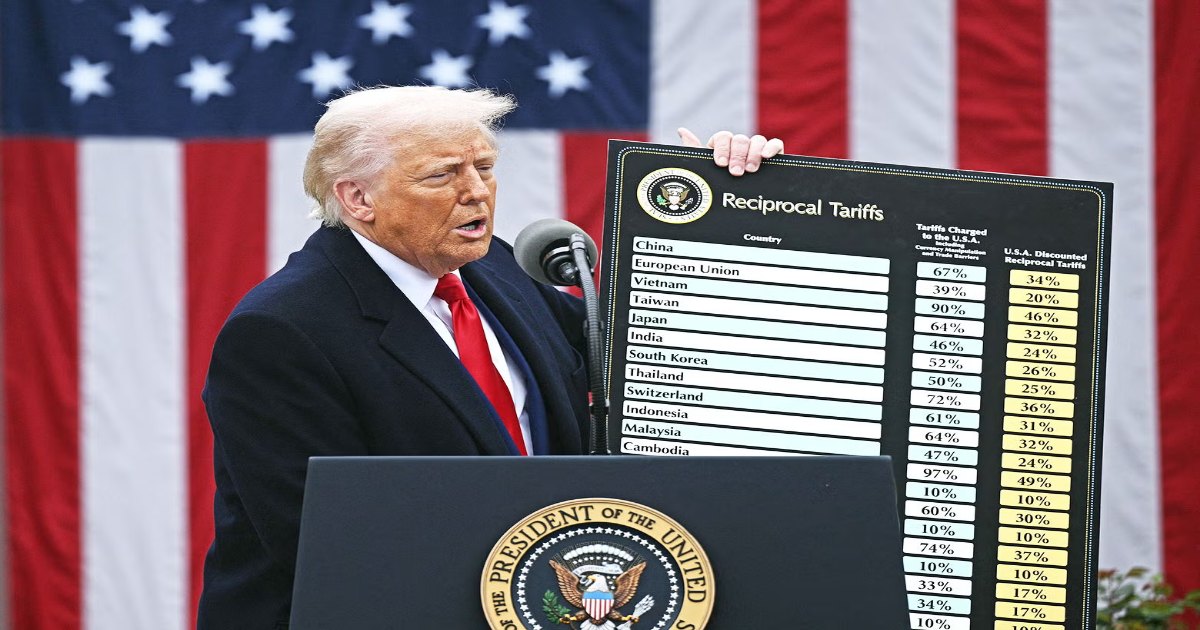

After we published that post, Trump went through with his promise and announced a huge new system of tariffs, individualized for each foreign country, that will tax almost all goods being brought into the U.S. at rates as high as 50 percent.

The president’s operating premise is that if a foreign nation sells more physical goods to the U.S. than it buys, it is “taking advantage” of Americans and that tariffs should be imposed on those goods until the balance equals out. The administration is also spinning the tariffs as an incentive for the country to rebuild its manufacturing and agricultural base: If it’s now super expensive to buy things abroad, the thinking goes, the market will naturally reward companies that can produce those things domestically.

But Trump has not taken any measures to prepare the U.S. economy to manufacture, for example, white undershirts; it is also impossible for the U.S. to produce some of the things it imports, like natural resources that don’t exist within its borders and foods that can’t be easily grown in its climate. Then you have the issue of why Americans would want to leave their current jobs for a worse-paying job in, let’s say, a shoe factory. (This is why prior political efforts to boost American manufacturing have focused on high-value products, like semiconductors, that can be built domestically.)

Long story short, American consumers can look forward to price increases, and American companies can look forward to consumers buying fewer of their products—not to mention other economic powers, like China and the European Union, limiting access to their own markets in retaliation.

So this is happening:

If there’s any silver lining to any of this, though, it’s that we’re getting some funny details about the, uh, robustness of the process that went into setting the new numbers.

- The ostensible premise of Trump’s tariffs is that they are “reciprocal,” i.e., issued in response to tariffs that other countries have already set on American goods. As part of the announcement, the White House issued data that purported to show the tariffs that other countries currently charge the U.S. But, as writer James Surowiecki first figured out, those numbers don’t have anything to do with actual tariff rates and in fact are just existing trade deficits turned into percentages. The example he uses is Indonesia, which in the most recent annual data exported $28 billion of goods to the U.S. and imported $10.1 billion. That means the U.S. has a $17.9 billion trade deficit with Indonesia, and $17.9 billion is 64 percent of $28 billion. The Trump numbers thus therefore claim that Indonesia is setting “tariffs” of 64 percent on the U.S. The logic, essentially, is that in a “fair” way of doing things, Indonesia would have 64 percent fewer exports to the U.S. The new “discounted reciprocal tariff” that Trump is imposing against each country—that’s the White House’s term, discounted—is just half of the deficit percentage, which is to say that the United States’ new tariff against Indonesian goods is 32 percent.

- As the Verge details here, a number of observers have noticed that this approach to calculating tariffs is exactly what a number of leading chatbots suggest if you ask them for an “easy way” to “level the playing field” between countries engaged in trade (or, to use the White House’s language, “balance bilateral trade deficits”). Two of the bots—Grok and Claude—even suggest cutting the resulting figure in half. (Grok is the chatbot developed by Elon Musk’s Twitter/X.) The White House did not immediately respond to a request for comment on the similarities.

- The executive branch’s official paper on the tariff calculations essentially acknowledges that Surowiecki is correct about how the White House arrived at the numbers, but it includes two other constants in the formula, which allegedly represent “elasticity of import demand” and “elasticity of import prices.” These constants are delineated in the statement by Greek letters epsilon and phi, which gives things an authentic academic feel. But the value of one of the constants, the administration has determined, is 4, while the value of the other is ¼, and they’re multiplied by each other. Which is to say that they balance out to 1 and thus have no influence on the actual result of the calculation.

- The administration’s list of entities affected by the new tariffs includes Heard Island and McDonald Islands, an Australian territory in the Antarctic that is not inhabited by humans but does have populations of penguins.

So the captains of U.S. industry, particularly those in Big Tech, convinced themselves over the course of the past several years that by collaborating with Trump, despite his hostility to democracy and the rule of law, they were poised to help rule a kind of Singapore-ized version of America—one in which they’d benefit from deregulation, lower taxes, and perhaps the suppression of labor and the press. Instead, they seem to have boxed themselves—for now, at least—into an American version of North Korea. Perhaps Grok can tell them what they should do next?

Sign up for Slate’s evening newsletter.

Sign up for Slate’s evening newsletter.