Mike White’s show wears its morality lightly.

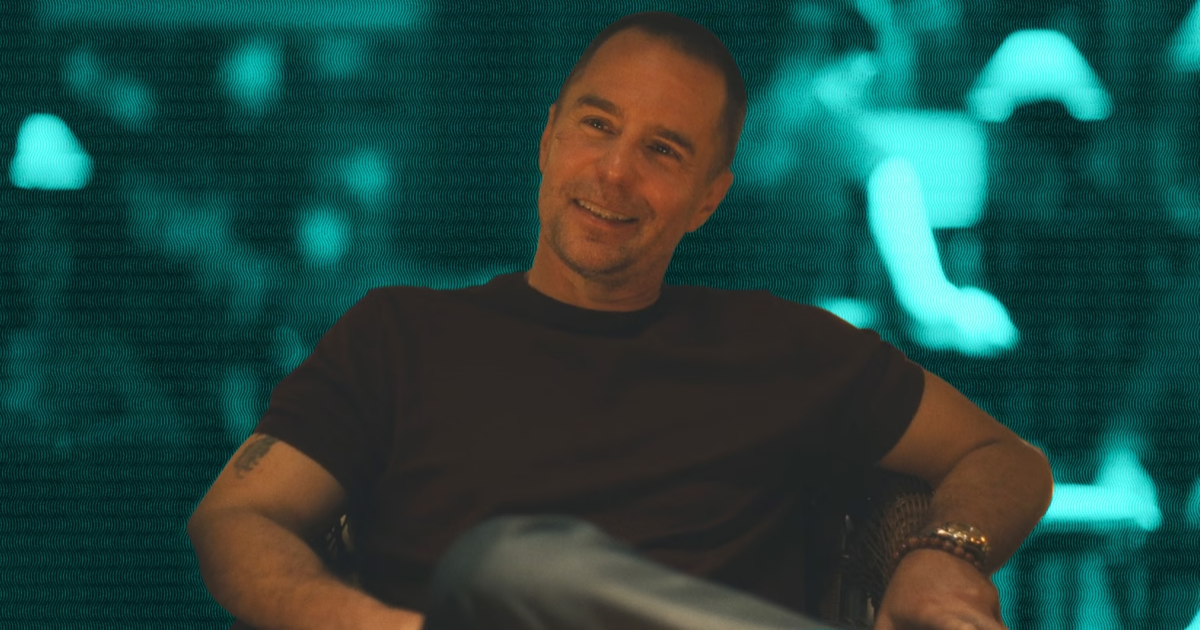

Illustration by The Atlantic. Source: HBO.

Mike White is not just the writer of The White Lotus. He is also its creator, director, and executive producer, and I’m surprised that he doesn’t do the catering and animal-handling, too. This unusual level of control makes The White Lotus the polar opposite of, say, the Marvel films, which feel like they’re written by one committee, edited by another, and marketed by a third.

And what has White done with his unusual level of creative control? He has made the first great work of art in the post-“woke” era. He treats his characters as individuals, rather than stand-ins for their identity groups—and he insists on plot points that would unnerve a sensitivity reader.

Hannah Giorgis: The rich tourists who want more, and more, and more

The White Lotus repudiates the “peak woke” era of the late 2010s, which yielded safe, self-congratulatory, and didactic art, obsessed with identity and language, that taught pat moral lessons in an eat-your-greens tone. Instead, White has made a point of discovering our last remaining taboos—kink, scatology, marrying for money, male nudity deployed so frequently in moments of high tension that culture scholars call it the “melodramatic penis”—and then putting them all on-screen, with a luxury hotel or a superyacht as the backdrop. If you’ve watched Episode 6 of the latest season, set in Thailand, cross Arnold Schwarzenegger’s son’s character has a drug-fueled threesome involving his brother off your bingo card.

But that scene—the explicit fraternal bonding between Saxon and Lochlan Ratliff during a hookup with the high-class escort Chloe—wasn’t the one that caused the most chatter among my friends. Far more shocking was a four-minute monologue in Episode 5 by a minor character, Frank (played by Sam Rockwell), that drew on one of the most incendiary findings in sexology: that some otherwise straight men are aroused by the thought of themselves as women.

In a bar in Bangkok, Frank explains to his old friend Rick (Walton Goggins) why he got sober since they last saw each other years ago. “I moved here because, well, I had to leave the States, but I picked Thailand because I always had a thing for Asian girls, you know?” Frank says.

At first, he took Asian women home for sex, but he began to find that boring. “Maybe what I really want,” Frank goes on, “is to be one of these Asian girls?” In a monologue punctuated by Rick’s occasional raised eyebrows, Frank describes how his behavior escalated. His quest for sexual satisfaction culminated in him buying lingerie, inviting white men over to “rail” him, and paying Asian women to watch them. This behavior led to a kind of spiritual awakening. “Am I a middle-aged white guy on the inside, too?” Frank wondered. “Or inside, could I be an Asian girl?” Eventually, he realized he had to stop “the drugs, the girls, the trying to be a girl.” So then Frank took up Buddhism—a religion that multiple characters in this season see as the antidote to Western materialism and their own obsessions.

Throughout Frank’s monologue, Rick looks perplexed—as well he might. But on X, Ray Blanchard—a real-life researcher who coined the term autogynephilia to describe men’s sexual arousal at the idea of themselves as women—expressed delight about the scene. Many in the LGBTQ movement have dismissed autogynephilia as a slur that reframes some trans women as nothing more than men with a fetish. Out Magazine recently described Blanchard’s idea as “a widely discredited pseudoscientific theory from the 80s.” And yet here it was being discussed on television’s buzziest show.

Suggesting that cross-dressing has a sexual component is even more subversive than, say, a graphic first-season sex scene featuring the hotel manager and one of his male employees. You might have thought that no taboos were left, but here is something as countercultural as Star Trek’s interracial kiss in the 1960s, or Ellen DeGeneres coming out in a 1997 episode of her sitcom, Ellen. Notably, unlike in the past, a screenwriter seems “brave” today by challenging liberals rather than religious conservatives.

Calling Mike White “anti-woke” makes him sound dreary and polemicist, when he is really irreverent and quietly moral. His father was once a ghostwriter for homophobic evangelicals such as Jerry Falwell and Pat Robertson, before acknowledging that he was gay himself in middle age. Mel White put his son through private school and college working for men who hated him for who he was. And then, when he had the financial independence to do so, Mel came out—but still joined Falwell’s congregation in Lynchburg, Virginia, despite the abuse that followed, and tried to convince his fellow Christians that religious faith and homosexuality could coexist.

Sophie Gilbert: The erudite, absurd White Lotus finale

Mel’s son had a different political trajectory. By his own account, Mike White once had conventional left-wing politics. He wrote an undergraduate thesis on Judith Butler, the high priest of postmodernism, when he was studying at Wesleyan University, which he has described as “the P.C. school, before institutions all became sort of like that.” In interviews, he has talked about how mind-blowing he found Camille Paglia’s Sexual Personae, a 1990 book that is deeply critical of feminism, defied what was then called political correctness, and contains bracing, before-its-time sentences such as “The reform of a college English department cuts no ice down at the corner garage.”

In the first season of The White Lotus, set in Maui, White pays Paglia homage: The snobby college student Olivia (Sydney Sweeney) has her book. Meanwhile, Olivia’s friend Paula (Brittany O’Grady) reads an anti-colonialism treatise by Frantz Fanon as native Hawaiians serve them cocktails by the pool. (Of course Paula also has a copy of Butler’s Gender Trouble.) In the second season, set in Sicily, Portia (Haley Lu Richardson) tries to talk herself into dating clean-cut Albie by observing that “he’s nice and smart. He went to Stanford, and—he’s not nonbinary.” White is mocking Portia’s world, in which so many students have minority sexual and gender identities that a standard-issue straight guy makes a refreshing change.

For that season, White created a cabal of murderous gay men—an offense against the liberal orthodoxy that movies and TV shows must portray members of disadvantaged groups in virtuous ways. Even though this plot was a huge hit with gay audiences, White’s gay villains made some cultural gatekeepers uncomfortable. “Barely anyone seemed triggered by White Lotus,” Beth Greenfield seemed to lament on Yahoo Entertainment.

Shirley Li: The sex lives of the one percent

In a recent discussion with White on his podcast, the gay conservative writer Andrew Sullivan decried Hollywood’s portrayal of gay characters, since the height of the AIDS epidemic, as suffering saints—as in the 1993 movie Philadelphia, which stars Tom Hanks as a doomed gay patient. Sullivan, who has written movingly about being diagnosed with HIV in the ’90s, praised White for allowing gay characters more emotional range. “I was hoping, you know, this was 30 years ago, that one day the gays will be presented as humans,” Sullivan said. “And so my big thrill, your second season of White Lotus, was the evil gays.”

White, who recently described himself on Sullivan’s podcast as a “guy who has sex with men,” appears particularly unconstrained in his portrayal of LGBTQ characters. In 2022, he said that “there’s a pleasure to me as a guy who is gay-ish to make gay sex transgressive again.” Frank’s autogynephilic liaisons with men and the Ratliff brothers’ incestuous threesome certainly fit into that category too.

What makes The White Lotus feel like the cultural product of a new era is that White doesn’t try to build shallow morality plays around these or any other characters. Nor does he drop in stock “Karens”—think of the way And Just Like That turned Sex and the City’s leads into idiot middle-aged ladies whom minor characters endlessly lecture about their outdated attitudes—whose primary job is to provide teachable moments. His plots and characters share elements from his own life. “Unless I feel somehow personally indicted, it doesn’t feel like I’m doing anything that bold,” he recently told The New Yorker. He bought a house in Hawaii after writing Enlightened, a series whose flaky lead character attends a rehab program there. He turned to Buddhist self-help books when he had a breakdown while writing a Fox sitcom, about an oddball family, called Cracking Up.

White’s most countercultural belief is that a heavy focus on identity is a prison, not a liberation. He told Sullivan that his time as an actor made him feel limited by his appearance, whereas writing allowed him to explore the way that “we’re all monkeys, first of all—we’re all apes—and we also share so much.”

Above all, his shows are fun—anarchic, dirty, humane. They have the message of 18th-century novels such as Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure, which lets readers revel in the filth of the prostitute Fanny Hill’s life before offering them the “tail-piece of morality.” Viewers crave yachts, and hot people, and terrible mistakes, and hot people making terrible mistakes on yachts. Give them that, and underneath you can smuggle the message that it’s all incredibly hollow and unfulfilling. After a decade when too many television shows had the tone of a Sesame Street episode on healthy eating, White’s formula of miserable rich people in sunny climates is a huge relief.

Helen Lewis is a staff writer at The Atlantic.